Spiritual traditions often spring from the soil in which they are planted, yet the fruits they bear may be surprisingly similar. Such is the case when one examines Franciscan spirituality, rooted in 13th-century central Italy, and the spirituality of the northern saints of Northumberland, which flourished in the 7th and 8th centuries in what is now northeast England. Despite geographical and temporal distance, both traditions radiate a strikingly kindred spirit—marked by simplicity, deep love of creation, humility, and a profound commitment to mission. At the same time, their differences illuminate the distinct cultural and ecclesial contexts from which they emerged.

Shared Foundations: Simplicity, Poverty, and Prayer

At the heart of both Franciscan and Northumbrian spirituality is a radical simplicity of life. St. Francis of Assisi (1182–1226) deliberately embraced “Lady Poverty” as a way of imitating Christ, stripping himself of all possessions, status, and power. This was not merely asceticism for its own sake, but a joyous relinquishment that freed him to be fully available to God and others. In a similar way, northern saints like St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (c. 634–687) and St. Aidan of Lindisfarne (d. 651) lived austere, simple lives. Cuthbert’s retreat to Inner Farne, where he lived in a small stone hut amid harsh weather and wild birds, echoes the Franciscan instinct to find God in humble, hidden places.

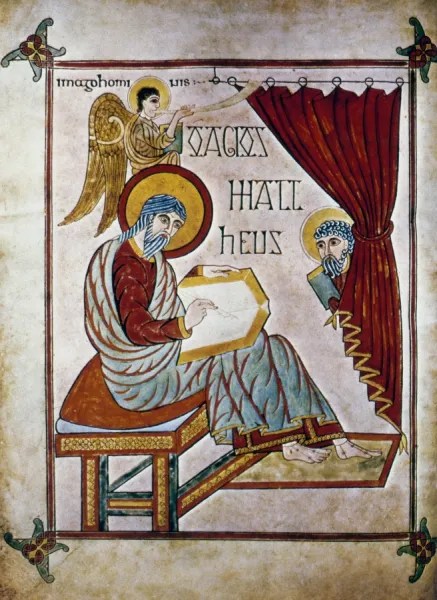

Both traditions also emphasize prayer as the centre of the spiritual life. For Francis, prayer was intimate and spontaneous, shaped by adoration, gratitude, and a sense of all creation participating in praise. His Canticle of the Creatures celebrates brother sun, sister moon, and even “sister death” as voices in the great liturgy of life. Likewise, the Northumbrian saints were steeped in the rhythm of daily prayer—drawing from the Celtic monastic tradition, which valued both structured liturgy and solitary contemplation. The Lindisfarne Gospels, with their intricate illumination and theological depth, suggest a community deeply devoted to scriptural prayer and artistic reverence for the Word of God.

Mission and Evangelism

A key point of convergence is the missionary zeal that animates both traditions. St. Francis famously received a vision in which Christ told him to “rebuild my Church,” leading him to a ministry of preaching, peace-making, and reconciliation. Though Francis had no formal power, his witness drew people in droves to a simpler, more Christ-centered way of life.

Similarly, Northumbrian saints were profoundly mission-focused. St. Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona, was invited by King Oswald to bring Christianity to Northumbria. Aidan chose to walk from village to village, rather than ride on horseback, as a sign of humility and solidarity with the poor—an approach that deeply resonates with Franciscan ideals. His spiritual descendants, including Cuthbert and St. Bede the Venerable, continued this gentle evangelism, winning hearts through example rather than coercion.

Love of Creation

Franciscan spirituality is famously ecological in its expression. St. Francis referred to animals and natural forces as his siblings, not as mere metaphors, but as genuine members of God’s family. This “kinship with creation” has inspired environmental movements even in the modern era.

While the Northumbrian tradition does not express this cosmic kinship in quite the same way, there is still a deep reverence for nature in the lives of its saints. Cuthbert’s affinity with animals—such as the otters who warmed his feet after prayer in the sea—mirrors the legends of Francis preaching to birds or taming the wolf of Gubbio. The wild landscapes of Lindisfarne, Iona, and Farne Island shaped a spirituality that was not separate from nature, but interwoven with it.

Communal and Itinerant Life

Another parallel lies in the balance between communal life and itinerant mission. Franciscan friars lived in small fraternities, but also took to the roads, relying on hospitality and preaching the Gospel wherever they went. Similarly, Northumbrian monasticism combined cenobitic (communal) life with missionary journeys. The monasteries at Lindisfarne and Monkwearmouth-Jarrow were centers of learning, prayer, and community—but their saints were often on the move, spreading the Gospel in gentleness and peace.

Key Differences

Despite their deep kinship, some distinctions are worth noting.

1. Ecclesial Structure and Sacramental Theology

Franciscan spirituality developed within the structure of the medieval Catholic Church, deeply sacramental and clerically organized. Francis himself, though a layman for much of his life, eventually submitted to ordination as a deacon and sought papal approval for his Rule.

The Northumbrian saints, particularly in the early generations, came from a Celtic Christian context that had different ecclesiastical practices. For instance, their dating of Easter, method of tonsure, and monastic structures were initially at odds with the Roman tradition, as seen in the Synod of Whitby (664). Although eventually reconciled, this tension reflects a more independent, localized approach to authority and sacramentality in the northern tradition.

2. Christology and Focus

Franciscan spirituality places intense focus on the humanity and suffering of Christ. The crucified Christ—poor, humble, and wounded—is the central image, leading to Francis’s reception of the stigmata in 1224. For Franciscans, imitating Christ means embracing the cross in love and joy.

The northern saints also venerated Christ, but their focus often leaned toward resurrection and light, shaped by the monastic rhythm of light and dark, the sea and sky. Their hymns and prayers—such as those preserved in Celtic tradition—emphasize the Trinity, the resurrection, and the ongoing journey of the soul. While both traditions honor Christ deeply, the spiritual “color palette” is slightly different: Franciscan spirituality is cruciform and earthy, while Northumbrian spirituality is luminous and mystical.

3. Artistic Expression

Franciscan art is characterized by its warmth, earth tones, and gentle realism—think of Giotto’s frescoes in Assisi. It’s an art of accessibility and intimacy.

Northumbrian spirituality expresses itself in interlace, symbolism, and sacred text—as seen in the Lindisfarne Gospels and Celtic crosses. This reflects a theology of mystery and transcendence that is less narrative and more iconographic.

Conclusion: Two Streams, One River

Though shaped by different centuries and landscapes, Franciscan and Northumbrian spirituality share a profound resemblance. Both traditions embody a Christianity that is humble, joyful, and deeply connected to the world around it. They model evangelism not through power but through presence, not by preaching alone but by living faithfully.

Their differences are not oppositions, but complementary notes in the great symphony of the Christian tradition. Where Francis sings of Christ’s wounds, Aidan sings of Christ’s light. Where Cuthbert prays in the wild sea, Francis chants with the birds in the trees. Both point toward the same God—radiant in humility, hidden in the poor, and alive in all creation.