Vocation Story

I always say that my sense of being called to religious community came after a friend gave me a copy of God’s Fool by Julien Green. The story of Francis really caught my attention, and I began to think about trying to live differently in the world. My major concern at the time was to try and live a radical Christian life. I was a school chaplain and paI rish priest (associate rector), and I was feeling it was too “safe and sane” for me. Just after I’d graduated from the General Seminary in New York I had lived in a homeless shelter and done outreach work for a parish in Times Square: forever after a benchmark of ministry for me.

Another reason I thought seriously about joining religious community was that as an ordained young gay man in the mid-eighties I was very lonely. I wanted family and community, and religious life offered that.

“God uses whatever we offer him,” Br. Derek SSF assured me when I shared my worries about the role of sexuality in my vocational discernment.

After about two years in the order I felt I would leave. I was struggling with a conflict I had in the community. On top of that, friends were publishing books, getting appointments to teaching posts, heading organizations, becoming rectors of parishes and I was jealous and felt my achievements were small potatoes—stretching a pound of hamburger mince to feed 6 people, talking with small groups of people, spending more time mopping floors than “using my gifts.” But I was intercepted by an older brother as one night I was sneaking out to leave. We had a heart-to-heart talk, and he advised me to wait until morning. Thirty years later, I’m glad he did.

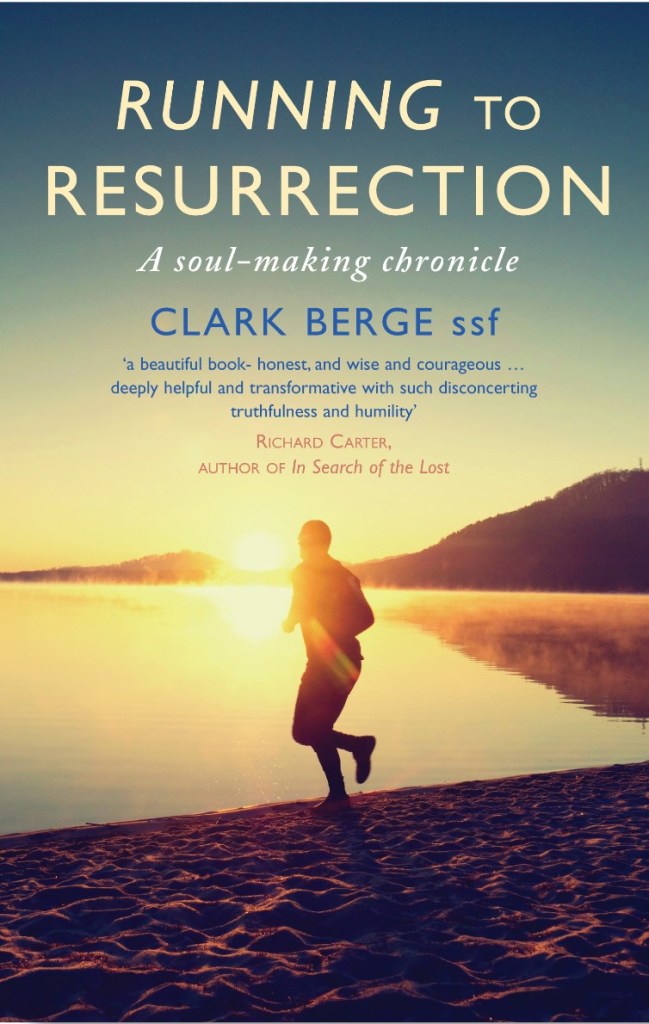

I haven’t had a struggle-free time in the Order, but I still find myself grateful for the life I have. I have had many experiences that I can honestly say would never have come my way. I lived for a year in the South Pacific on an island. I have run a medical clinic, written books, served many people as a spiritual director, competed in a marathon. And I still try to stretch the food to feed all comers, do my part in the endless round of housekeeping.

The joy of those small groups I end up talking to about St. Francis is that I am always re-considering the example of Francis and my response to a call to live the Gospels. Discernment is never-ending. Its unfolding. My gifts and wounds have become part of what I offer. The main thing is receiving what God is offering to me through my brothers and the places and situations in which I find myself.

Tools for transformation

Prayer, study, and work are the foundation of the religious life, and as the Principles of the First Order of SSF say ‘room is to be found in the lives of all for at least some measure of each of these three employments.’ Yet I find the effort to keep these three areas of service in balance a difficult, sometimes impossible task. Nevertheless the struggle has illumined a way of life that has always been the Christian vocation; perhaps my story can illumine the theological and personal issues for others. I find it interesting that when I think of the three ways of service, I say ‘work, study and prayer,’ instead of the other way around as they appear in the Principles. I feel caught out as a workaholic and the product of the American work ethic.

The tension underscores the problems inherent in compartmentalizing life into discrete functions: it leads to what we call burn out! Integrating our life is the greatest invitation in our Franciscan way of life. One of my first spiritual directors gave me Brother Lawrence’s The Practice of the Presence of God. It seems to me that the lasting contribution of Brother Lawrence to the spiritual life and prayer is the way in which he reframes menial tasks: cooking and cleaning to the glory of God. Running a retreat house with only a few brothers and occasional paid help, there are always things to be done. When I do them angrily, I have little energy for prayer, and no energy left over for those precious moments of free time.

Recently, I was discussing with a guest the things we like and don’t like about everyday life. I said how much I hate scrubbing toilets: it has always seemed to me to be demeaning work. Hearing that, this professional business woman laughed, saying that cleaning toilets was her favourite task because in doing them she could let her mind relax; she could allow the repetitive movement to jog her mind into a prayerful place. Her words came back to haunt me when I later found myself attacking the toilets with an aggrieved attitude. How I think about my work makes a big difference to how I feel about it. Linking work with prayer may be the only way to reduce stress and enrich my spiritual life, ‘seeking to serve my Master . . . within the house and garden.’ Part of my attraction to the religious life was that I would have guaranteed time for prayer. What I have discovered is that I have to make a conscious decision to pray.

The Principles articulate an ideal and certainly nobody ridicules the idea that I need to make time to pray. But I was unprepared for the insidiousness of the ‘formal and careless spirit’ mentioned by the Principles. I can’t remember ever rejecting God or prayer, but I vividly recall deferring prayer, saying I’d get to it later, for whatever reason. A few years ago I lost extra weight by choosing how much to eat and to get more exercise, although for most of my life I have resisted the advice of anyone who tried to influence what I ate or how much exercise I got. Discipline is a choice; I have to choose to develop a desire to pray or connect with God when I lose the thread of my prayer life. There have been times when I’ve fooled myself into thinking that the daily office and mass were a rich prayer life, but without an inner desire for God the rituals only cloak a growing emptiness. Another pitfall is what I have learned to call ‘process skipping.’ I skip over the feeling dimension, keeping my prayer in my head, analyzing rather than feeling and praying. When I am stuck in prayer it is often because I am not paying attention to what I am feeling; by not recognizing the feelings in my prayer, they have crept out in compulsive behaviour and overwork. Reality only intrudes during a crisis, when my carefully groomed image of self control snaps and I do something I deeply regret.

I resigned from a position as a director of a mobile medical unit serving adolescents at risk from HIV after I swore at one of the outreach workers simply because he was in my way. I remember walking back to the friary thinking ‘where has it gone wrong?’ My life had become unmanageable, and I’d lost a sense of conscious contact with God. Resigning wasn’t an answer to my problem; it’s one I have had to visit repeatedly since. Recognizing the issue seems to be the big first step. My prayer life seems to consist of discovering the same truths over and over again, asking God for help, over and over again. Looking at my bookshelves is another way of tracking the issues in my life. Novels predominate, but there are also a lot of books about sexuality and selfhelp books dealing with stress and time management from Christian and spiritual perspectives.

I don’t have a favourite author, or even one particular book that helps me understand the ‘soul’s ascent to God,’ but the mix of stories and insight nourish my understanding and desire for a healthy and sane life. For a classic bookworm, the real work of study comes from the difficult task of talking with others and hearing what they have to say. For most of my life I’ve had the smug sense that I am right. I always preferred to work alone in school; when teachers would put us into groups, I would immediately divide the task into parts and assign responsibility for each part, so that I could do my part, alone. I think pretty well, but my best thinking has gotten me into some pretty unlovely scrapes. Opening up myself to others in a safe environment I have learned to think creatively, and to recognize how others who struggle to live a healthy life often grapple with the same issues as I do. Our bible study at Little Portion is just such a time. The effort is to identify the patterns of the scriptural stories in the world around us and in our lives; and then to tell our stories to each other. It is a humbling thing to hear how others feel God is working in their life, and then to reflect on my life. This social dimension of study, divorced from the monkish archetype of solitary study in a lonely cell has taught me to think in many new ways.

The American Province has also begun trying to help brothers identify what it is they want to learn about and facilitating the learning process. Conferences, workshops, and the website amazon.com are familiar features of our life, and essential to our work of study in learning to better serve ourselves and others. Prayer, study and work are the tools for transformation, the way we equip ourselves to serve the world. In conversation with God, other people and ourselves as we bend our backs to cleaning up corruption or toilets, our conventional thinking is challenged and new ways are opened up.